Today was the day we left before sunrise – the air still cool, the sky just beginning to shift, and made the journey by plane to Abu Simbel.

Even knowing the photographs – nothing prepares you.

The statues of Ramses II rise from the rock like something emerging from the earth itself. Monumental. Commanding. And yet human in a way that is difficult to articulate.

The temples are astonishing.

Carved directly into the cliff, four colossal statues of Ramses II sit watching the desert like guardians of time.

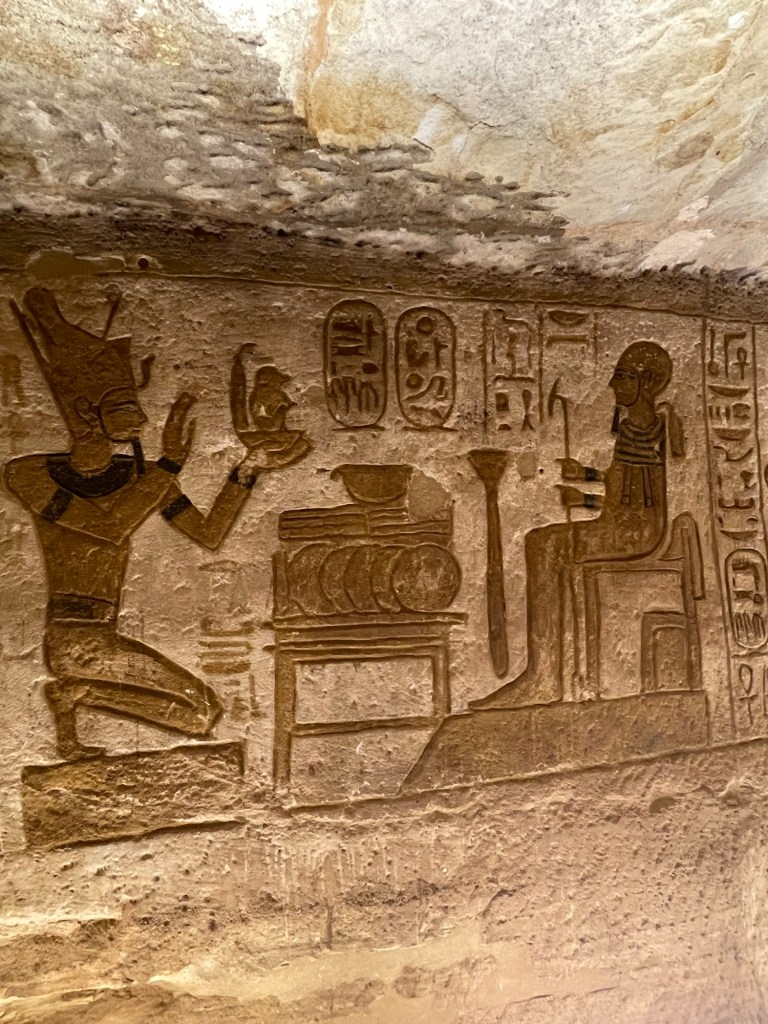

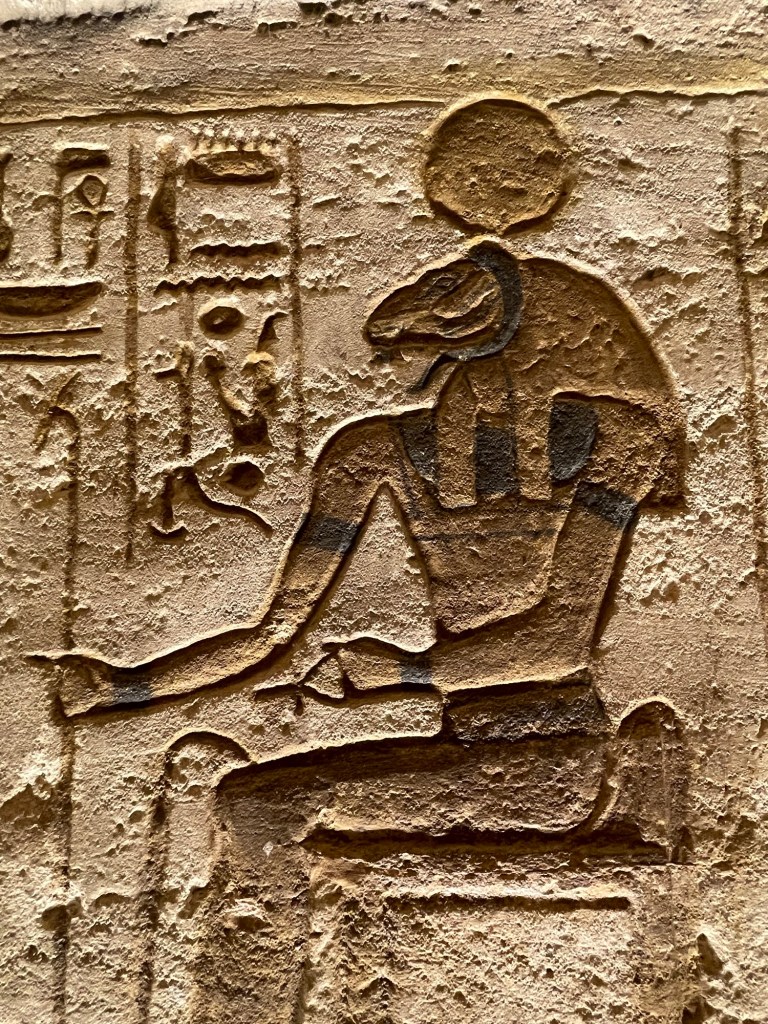

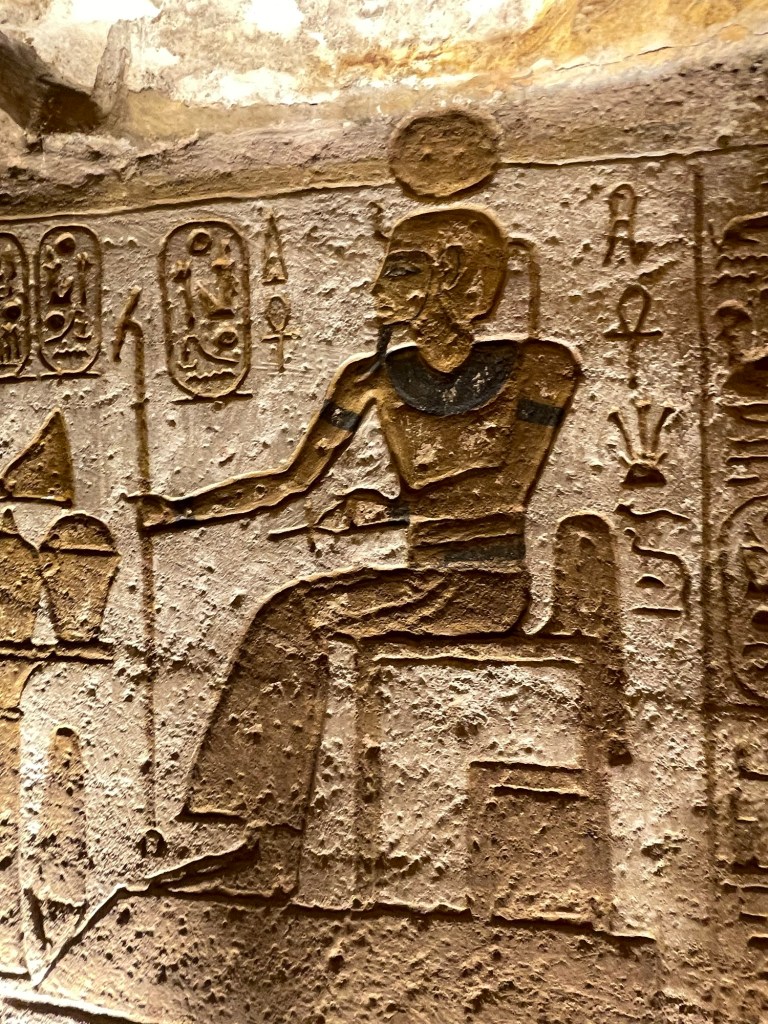

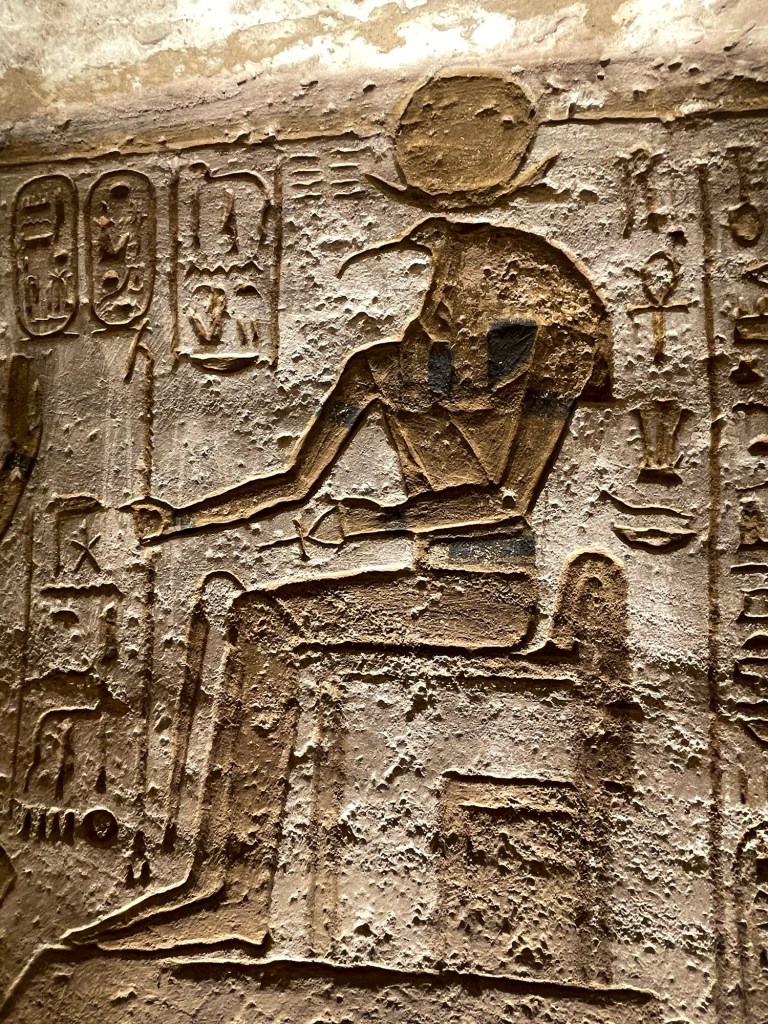

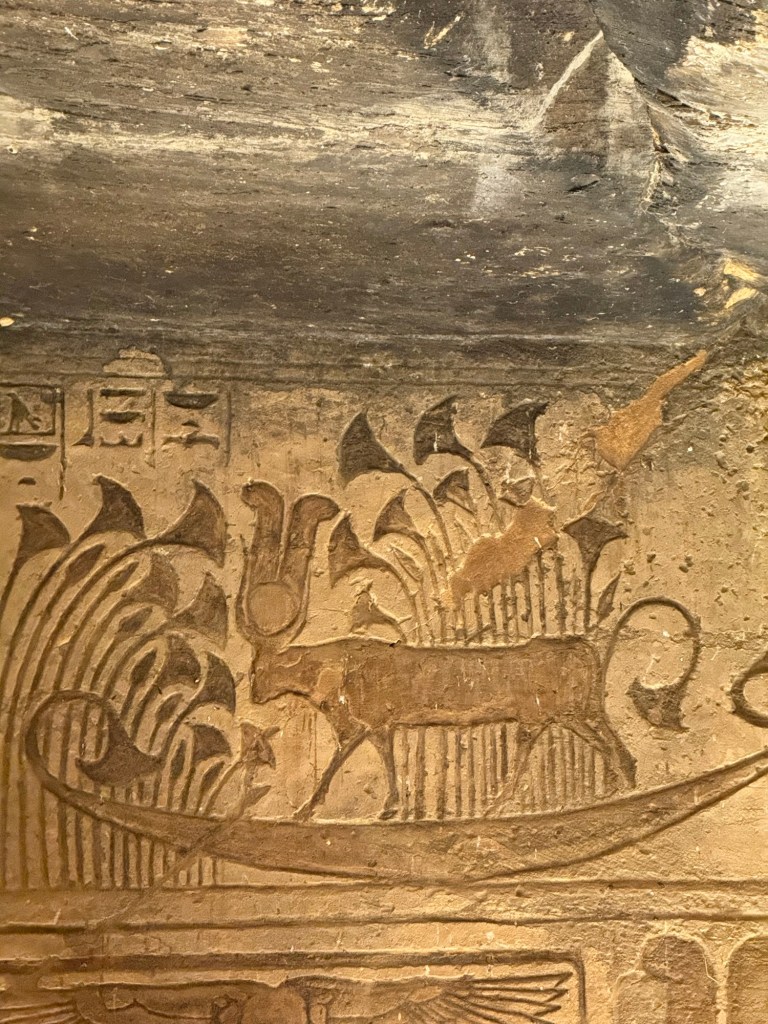

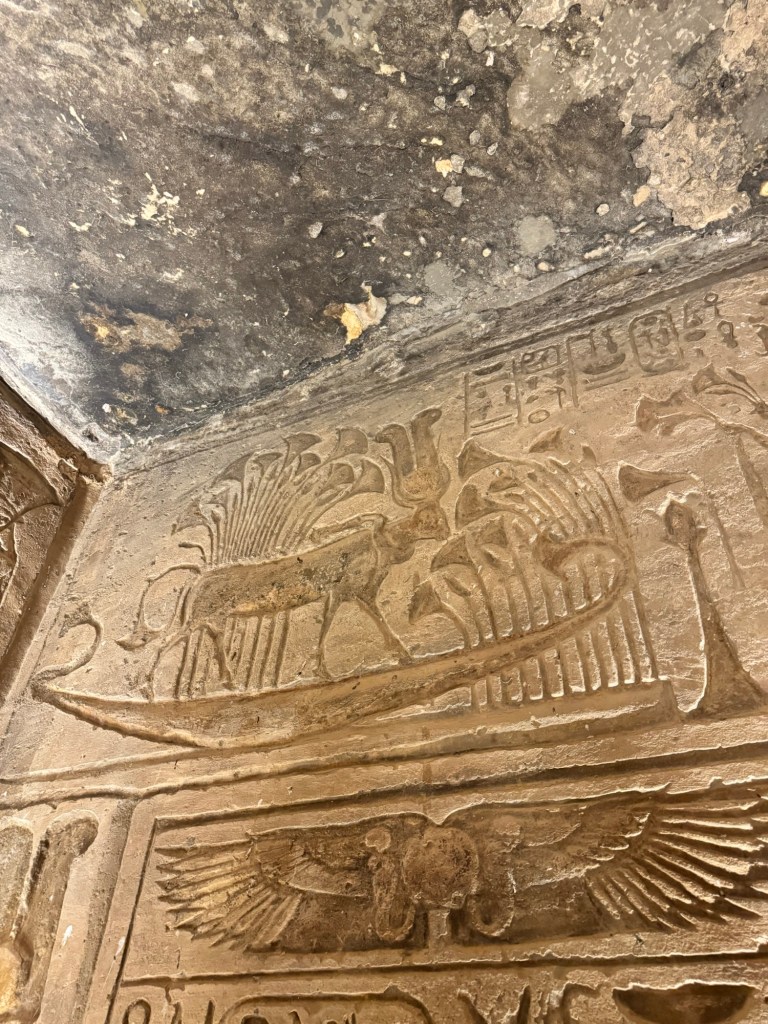

Inside, the halls are lined with reliefs celebrating victories, gods, and eternal life—but what struck me most was the feeling of scale, both physical and emotional. This was made to endure. And it has.

The carvings are vivid, rhythmic, ceremonial. The temple feels like it was built to be remembered.

Temple of Nefertari

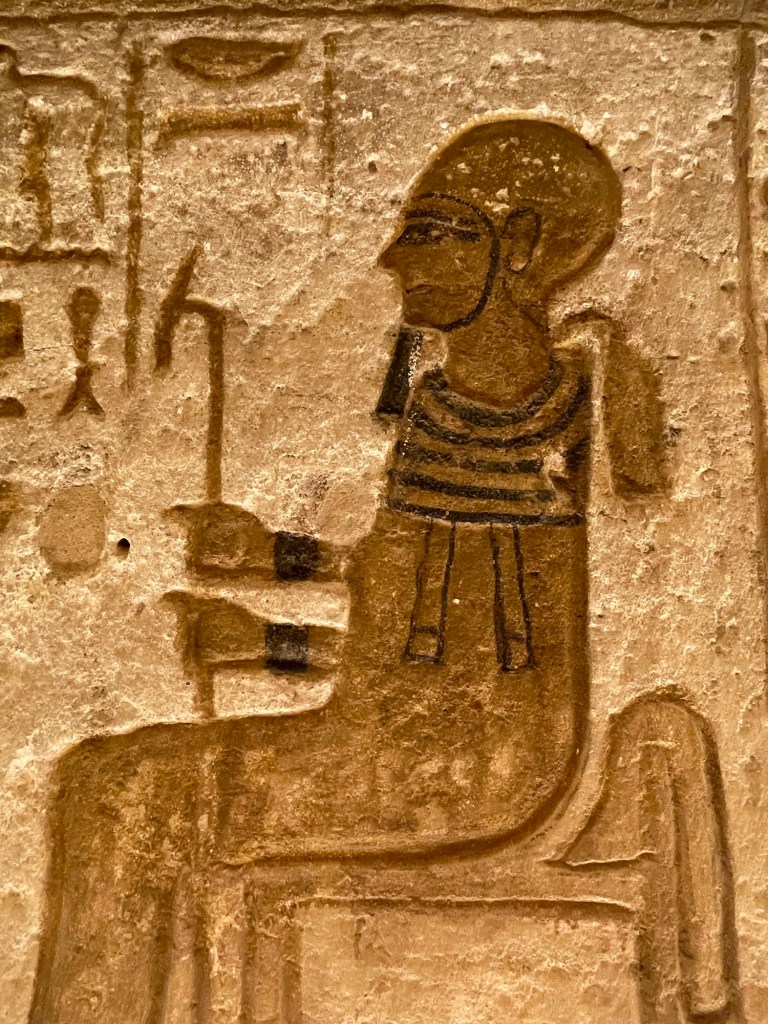

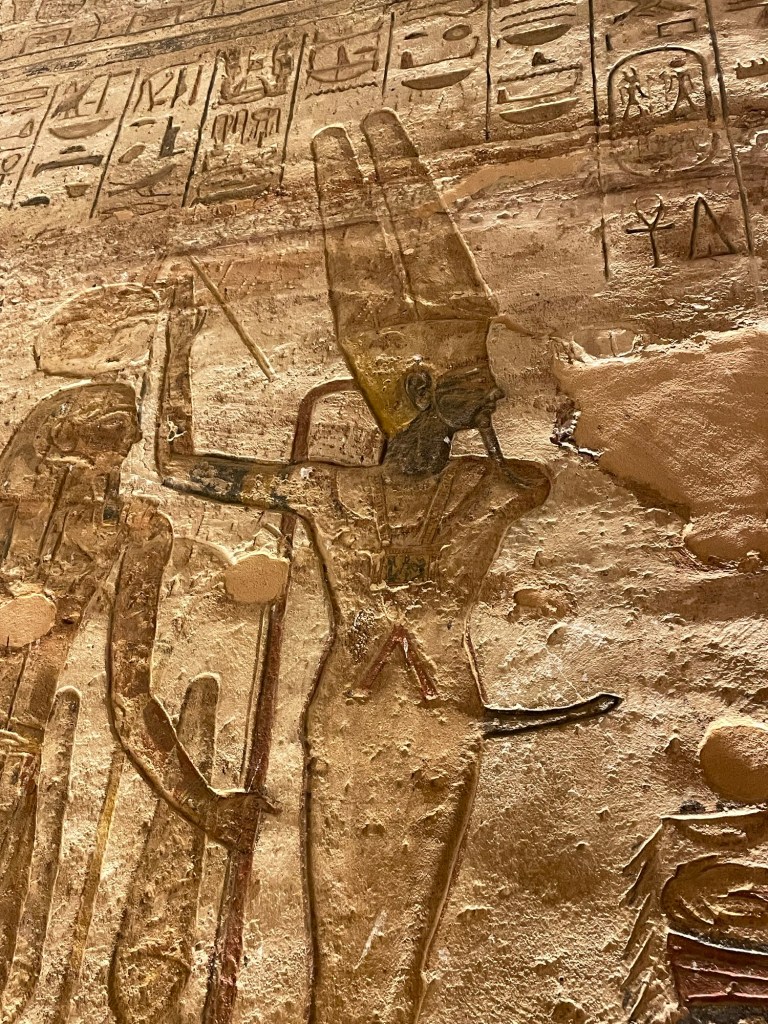

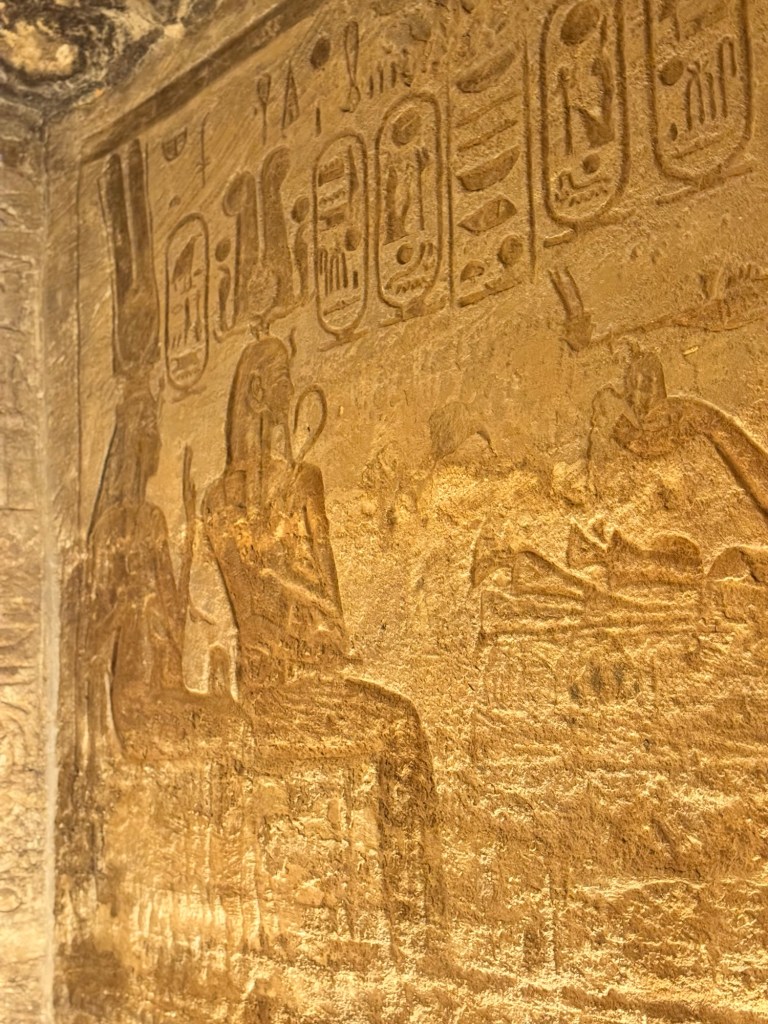

Rameses II didn’t just build a temple for Nefertari, his beloved wife, he carved his devotion into stone. At Abu Simbel, her temple stands with a grace that feels almost tender beside the colossal bravado of his own. The façade shows her not as a footnote to a pharaoh but as his equal, standing shoulder to shoulder with him in a way no other royal wife ever was.

Inside, the walls tell a quieter story: Nefertari as beloved queen, musician, diplomat, and confidante.

You can feel his affection in the way her image is repeated, honoured, illuminated. In a world where monuments often serve power, this one feels like something rarer: a husband’s attempt to make his love eternal.

Moving the Temples

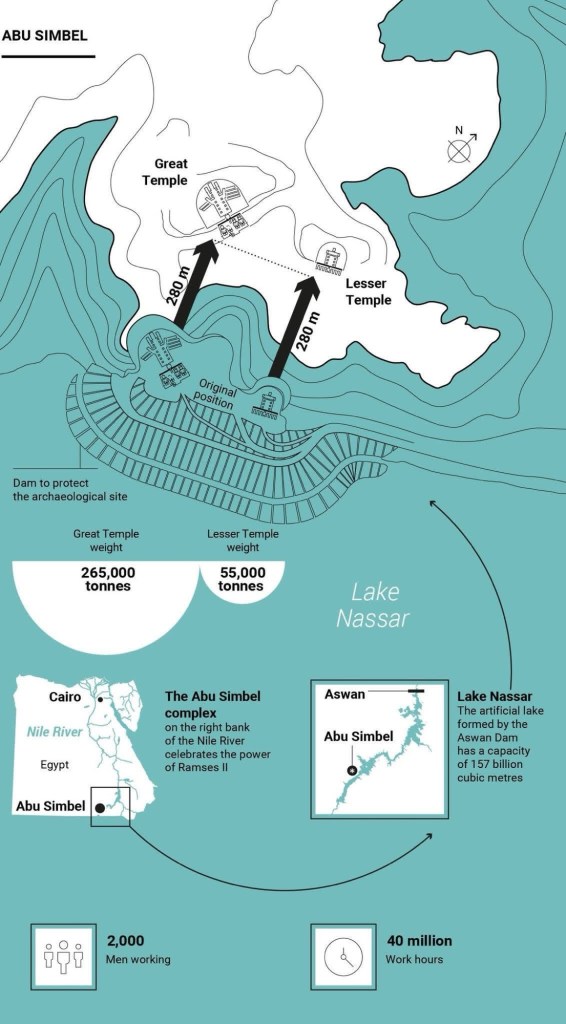

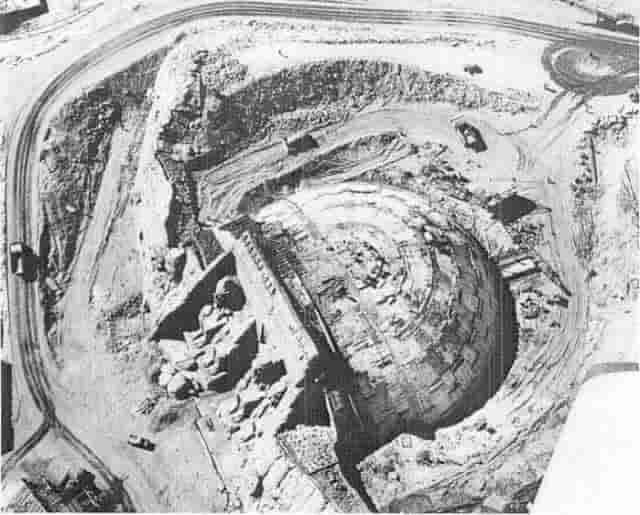

In the 1960’s, they moved these temples 65 metres higher than their original position, block by block, to save them from destruction when the rising Nile waters from the construction of the nearby Aswan High Dam, threatened to put thousands of years of history at risk.

The first photo shows the temple as it is today…

The following photos show its relocation.

You can see a schematic cross-section of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel.

The diagram illustrates the architectural features and the modern reconstruction method used for the temple.

The new location of the temples looks very much like the old. A concrete dome protects the interior as the rocky hillside surrounding the temples was recreated.

The temple was rebuilt with the same orientation, so that twice a year, the rays of the rising sun strike the seated statues in the rear sanctuary.

The return to Aswan was quiet – the kind of quiet that follows awe, and also because the 4am wake up and the unrelenting heat and humidity inside the temples, completely zapped us all.

Nubian Village

One of the things I’d most been looking forward to was visiting the colourful Nubian village. It wasn’t on our itinerary — apparently many guests had raised concerns about the crocodile shows some operators run over there, so the cruise quietly dropped the stop. I wasn’t interested in any shows; I wanted colour. When I left Marian, I’d been given a Camilla voucher, and I bought a dress patterned with the same bright geometric motifs painted across Nubian houses, cafés, and shopfronts. I’d been dreaming of seeing the real thing.

Thankfully, our ship host worked some magic and arranged an escort and a small boat to take us the 45 minutes upriver.

The moment we stepped ashore, the village felt like a burst of joy — houses washed in turquoise, fuchsia, lemon, and terracotta, their facades decorated with symbols of the desert, the river, and family heritage. We wandered through part of the village, stopping for photos and gracefully dodging the persistent but good-humoured market vendors.

If I hadn’t felt on the verge of vomiting since lunchtime, I probably would’ve lingered longer, browsed the stalls, maybe even haggled for a few of the bold African textiles. Instead, I focused on smiling and looking remotely glamorous for Josh — my unofficial Instagram boyfriend — who, to his credit, delivered some excellent shots despite my green-around-the-gills energy.

The Nubian people themselves have called this region home for thousands of years, long before pharaohs carved their legacies into the cliffs. Traditionally living along the Nile in southern Egypt and northern Sudan, many Nubian communities were displaced in the 1960s when the Aswan High Dam created Lake Nasser. Entire villages were submerged, and families were relocated to the islands and west bank around Aswan. Even after all that upheaval, their culture — warm hospitality, vibrant art, music, and a language unlike Arabic — still thrives, bright and resilient as the colours on their walls.

By the time we made it back to the ship, the nausea had won. I collapsed into my cabin and couldn’t make it to dinner; I was too sick to even sit upright. The entire night was waves of queasiness and regret that my dream visit had collided with my worst travel timing. Still, in the flashes between stomach lurches, I held onto the colours — proof I’d made it there at all

Tonight, I tried to rest and recover.

Tomorrow, the river turns back toward Luxor and there is one more temple to see and I’ve been looking forward to this one.